In the comments below, please submit questions for me to answer via podcast.

Podcasts will be posted here. You can also find the link at the top of the left sidebar. You can sign up with iTunes or RSS to get notifications.

In the comments below, please submit questions for me to answer via podcast.

Podcasts will be posted here. You can also find the link at the top of the left sidebar. You can sign up with iTunes or RSS to get notifications.

Twitter is now borderline unusable. Recently a tiny popup on my iPhone let me know they were no longer showing me the most recent tweets of the people I follow. Instead they would show me tweets of their choice. Twitter has a new algorithm where they control what you see. That sounded awful. Although they defaulted me to using the new algorithm, I was able to change back to reverse chronological. I thought everyone was OK.

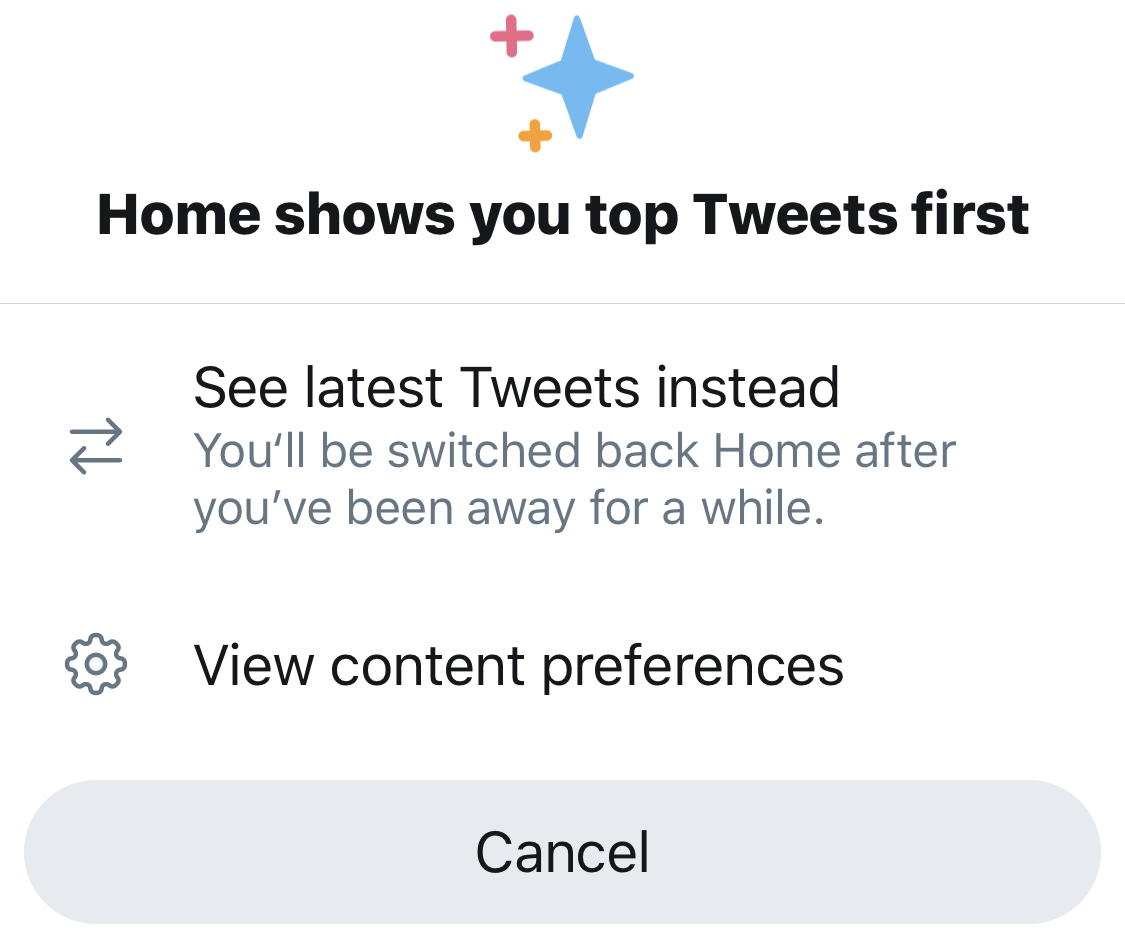

But I later noticed I was not getting reverse chronological tweets. It turns out Twitter named the new algorithm "Home" and says you periodically get switched back to "Home" – that is, not only did they default-opt-in the new algorithm, they set everyone back to it every few days(?). The text explaining this is intentionally weird and unclear. It means: you can't opt out of the new see-what-Twitter-wants algorithm for long.

A day or two ago I set my feed back to reverse chronological, again. Today I saw this:

The top tweet is not the kind of thing I want on my feed. I wondered: who do I follow who would retweet that? I might want to unfollow them because we have different tastes. But the answer is: no one.

By happenstance – perhaps this is common with the new algorithm – the other two visible tweets were also ones I didn't want to see. There's another one that wasn't retweeted by anyone I follow. And then there's an ad by Apple (I like their products but I don't like their tweets and don't follow them on Twitter, it says it's a "Promoted" tweet if I scroll down a little past the screenshot).

It's kind of like the people you follow are your Twitter family, and Twitter now shows you tweets from uncles, cousins, and brothers-in-law. But it's not just any tweets from you extended Twitter family you didn't ask for and can't get rid of, it's the ones that biased, left-wing Twitter wants you to see.

What do I do now? I carefully curate who I follow in order to get a decent quality timeline with a high signal-to-noise ratio. Now Twitter has taken that away from me. I can change it back to the "Latest Tweets" setting but Twitter will repeatedly, automatically switch it back again to "Home" aka "show me whatever Twitter prefers I see". It was bad enough when Twitter started showing me an algorithmically-biased selection of tweets that were Liked by someone I follow, but at least that was a choice they made (someone I follow decided to hit a button), even if it wasn't actually the choice to broadcast that tweet. Now maybe I can only follow people who, in addition to tweeting good content, also keep a short, curated follower list which matches my tastes.

I guess I'll get a third party Twitter client even though I don't want any extra features and Twitter has been hostile to alternative clients for years.

David Horowitz has a comments forum for his Black Book of the American Left:

I welcome comments on the Black Book and will reply to as many as I am able. I especially welcome comments from the left which so far has pretended that this critique does not exist. This is a throwback to the Stalinist era, and I hope that there are some leftists with the integrity to attempt to meet an argument rather than stamping it out. I hope all commenters will treat the intellectual issues involved and not resort to name-calling and anti-intellectual rants.

And below, above the fold, one can read his extended, serious reply to a leftist whose insults had included: “crazy,” “delusional,” “waste of energy,” and “nonsense”.

At this “forum” for his book series, Horowitz seeks feedback and discussion, especially if anyone has a reasonable/serious criticism. It’s a Paths Forward page!

I’ve long noticed the best people tend to be particularly open to discussion, even if they’re high status and busy. I already knew Horowitz talked with people on Twitter. Rand, Feynman, Popper and others answered letters in the mail in addition to all the effort they put into having conversations with people in person (e.g. Rand routinely invited over groups of people for many-hour discussions). And now with the internet, I’ve found people like Deutsch and Szasz far more accessible online than other, inferior intellectuals.

The reason for this is that smarter people are less fearful of criticism, and actually have a confident and eager attitude regarding learning new things and correcting their errors. And the better people are more capable of explaining what they mean and communicating well, and also value practice communicating. The best people also are curious in general, and interested in what the world is like and what people think – and they have the capacity to think about that instead of being overloaded just from trying to do the minimum requirements of their career.

This method is not at all an exact method for judging people (which isn't the point, the point is about the importance and value of discussion). But interest in discussion and criticism is a big deal. And anyone who says “I get plenty of great, critical discussion through private channels” is a liar. There is a shortage of quality discussion in the world, and no one has access to a bunch of great private conversations to the extent that it no longer makes sense for them to use any publicly visible resources. There is no hidden reserve of really smart people for the famous people to have secret access to. That is a myth.

The UK government spends money to buy new slippers for the elderly to try to protect them from slipping and falling.

Giving people free slippers should be voluntary charity rather than taken from tax payers.

But I don’t think it’s a good idea for voluntary charity either.

Why do non-cash charity? The reasonable reason is there are advantages to distributing used items instead of selling them then distributing the sales profits. But in this case they're buying new slippers.

Charities distribute new items, instead of cash, because they know that if they handed the person cash the person would not buy the items being distributed. It’d be easier to hand out cash than slippers, and then people could buy their own slippers (and make a better, more-personalized choice about the size, style, etc). But most of these people would prefer to buy something else other than slippers.

Giving someone something that he values less, instead of something he values more, is an attempt to control his life. It’s paternalism. It’s saying his preferences are wrong and you want to change his life to be more how you think it should be. And it’s not arguing or debating that point, it’s just using the position of power (as the charity with the wealth) to pressure people.

In general, if you want to most help someone according to their values, you give them cash and they buy what they value most highly. Non-cash charities giving out new items are clearly not aiming to maximize how much they help people according to the values of the person receiving the help. They are instead, to some extent, trying to impose their own value systems on the charity recipients.

Charity for slippers and other similar things also creates perverse incentives. It discourages buying slippers. The government will give you new slippers but it won’t give you a Switch, so it encourages you to buy a Switch instead of slippers. And if the next slipper swap is in 3 months, then the government is encouraging you to use your old slippers for 3 months (the exact thing they claim is dangerous) so that you can get free slippers instead of having to pay.

If the government and private charities give enough kinds of specific aid – clothes, food, housing – then they can really encourage some poor people to spend their money “irresponsibly” to get a nice couch, a big TV, etc. The more they spend on the things the government and charities consider important, the less charity they receive, so they are encouraged to get in the habit of buying cigarettes, alcohol and anything else the government would never give them, rather than spending on food and clothes.

PS Here’s some more government involvement with slippers. Some shoe companies put a thin, cheap layer of felt on the bottom of their shoes, which is meant to quickly wear out. Why? Because if the bottom is felt instead of rubber, then it’s a slipper instead of a shoe, which can reduce tariffs from 37.5% to 3%. This is a waste of felt and effort. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/this-is-why-your-converse-sneakers-have-felt-on-the-bottom-6016648/

Powerful people make biased decisions all the time. People make rules like “Don’t be influenced by sex, make the decision that is best for the company, e.g. promoting the most qualified person.” These rules are very hard to enforce.

How can you reduce bias? Instead of prohibitions, have people explain their reasoning and have some criteria it should use. And require them to answer a sample of criticisms/counter-arguments, including some chosen randomly and some chosen by adversaries.

This makes it harder to make a decision for sexual reasons. If you do, you still have to write about other reasons. You have to think through the other reasons. And then you have to lie and try to argue a case you know to be false. The more egregious the error (appointing someone really unqualified, say), the harder this lying will be.

Perfect system? Not at all. People will write (or say it in a speech) vague, generic, low-content bullshit about how Lacy exemplifies all the characteristics that official constitute being qualified. So don’t ask him to judge vague things like if someone is smart or hard working, make more of the decision about more measurable factors. Or just suffice it to say that if the audience is gullible then procedures don’t really matter, but if the audience can see through vague bullshitting then the guy is going to struggle with the requirement to address criticism.

If you give someone the leeway to promote anyone whose qualifications round to “qualified” in the eyes of an imprecise, gullible audience then you are not going to get the most qualified candidate promoted very reliably. Too bad. Don’t blame the guy in charge. Give people less leeway for decisions, or make them respond to arguments from more discerning audiences, or stop complaining when they are biased.

There are a million sources of bias. People are wrong to try to tackle the bias problem by focusing on a couple well known sources of bias and trying to suppress those (largely in ways that you can’t judge very objectively, so enforcement ends up being either non-existent or arbitrary/capricious and even more biased than the original problem you were trying to fix, which is especially bad cuz now the stakes are firing people and attacking their reputations, whereas the stakes before were more like someone failing to get a promotion and someone else gets it and the person who gets it is qualified within the error bars of the level of discernment of the audience. The audience is at least like the boss’s boss has to not find the behavior ridiculous, even if none of my proposals are used. And even the CEO is often accountable to the board of directors or investors).

We need anti-bias procedures that have reach/generality, that work on tons of types of bias (even ones we haven’t thought of) at once. Making a rule against sexual favoritism doesn’t do that. Maybe that particular rule is fine and worth having, anyway, given the current cultural situation and history (well, I think maybe that kind of rule was good 50 years ago, but today it’s politicized and being used to ruin a lot of lives that I don’t think merit ruining).

The big picture is we are all alike in our infinite ignorance (as Karl Popper said), we are at the beginning of infinite progress (as David Deutsch said), there are infinitely many ways to make mistakes, and prohibiting a list of known mistakes is a poor tool for addressing this. If you really want to do something about bias, you need procedures that oppose many large categories of bias at the same time. Having people say their reasoning and answer some criticisms makes bias generically more difficult because any bias could be criticized and also it makes it harder for the decision maker to be thoughtless – in order to make a halfway convincing case about why he’s making a good decision (as judged by the publicly desired decision criteria) he has to actually think about what a good decision is supposed to be. People do have some integrity, and lots of people try not to be biased and would change their decision after conscious analysis (and the larger the deviation from the truth, the more people will be unwilling to do it if they’ve actually thought it through and seen that for themselves).

Relying on the critical faculties of the decision maker and the audience may sound like weak enforcement. It is. But there's no way to get strong enforcement or guarantees. If the people involved are too dull to spot blatant errors, then those errors are going to happen. Thinking is always our defense against error. If people shared reasoning and answered criticism, it'd give critical thinking a better opportunity to be effective. It'd improve the status quo where people often hide their reasoning while knowing it'd be difficult for their reasoning to stand up to scrutiny, or don't even think things through since they won't have to share their thought process.

See also: Using Intellectual Processes to Combat Bias

PS These thoughts are partly a comment on Robin Hanson’s tweet asking about a powerful man helping a career of a woman he has sex with.

In Can Foundational Physics Be Saved?, Robert Hanson proposes prediction markets to evaluate the future impact and value of scientists and research. This is intended to help address cognitive biases and incentive problems (like overhyping the value of one’s own research, and seeking short term popularity with peers, to get funding and jobs).

Markets strike me as too much of a popularity contest where outlier ideas will have low prices. I don’t think letting people bet on things will do a good job of figuring out which are the few positive outliers out of the many mostly-bad outliers. Designing good, objective ways to resolve the bets and pay out the winners will also be very difficult. And historians are often mistaken (in many ways, even more so than the news, which often gets the facts wrong about what happened yesterday), so judging by what future historians will think of today’s scientists is not ideal and can differ from what’s actually true.

So, in line with Paths Forward (including the additional information linked at the bottom like Using Intellectual Processes to Combat Bias), I have a different idea about how to improve science. It is online discussion forums and a culture of answering criticism.

Scientists and research projects should explain what they are doing and why it makes sense, in writing, and anyone in the public should be able to post criticism. Basic standards for discussion tools are listed in footnote [1].

Most readers are reacting by thinking discussions will be low quality and ineffective. There are many cultural norms, discussed in the linked essays and in books, which can improve discussion quality and rationality. But that’s not enough. People can read about how to have a truth-seeking discussion and then still fail badly. There already exist many low quality online discussions. Why, then, will the ubiquitous use of discussion venues help science?

Because of the expectation of answering every criticism received.

This often won’t be done. What’s the enforcement? First we’ll consider the vast majority of cases where a researcher or research project doesn’t get much attention. A few forums will get too many posts to answer, and we’ll address that later. But suppose some obscure scientist receives one criticism on his forum and ignores it. Now what?

Today, if I find a mistake by a scientist, I can write a blog post explaining the issue and arguing my point. Then I can tweet it out, share it on popular discussion forums, and hopefully draw some attention to it. What will people say? Many will try to debate. They will agree or disagree with my criticism. The Paths Forward approach will transform this situation into a different situation:

I write my criticism and post or link it at the discussion forum for the scientist or research project. They ignore me. Then I say to people: “I wrote X criticism and the relevant scientists did not respond.” And no one then debates with me whether my criticism is correct or not. That doesn’t matter. Everyone can clearly see the scientist has violated truth-seeking norms whether my criticism is correct or not. “He did not answer X argument…” is much more objective and clear-cut than “He is wrong because of X argument…”

Norms of having open discussions, where criticism is expected to be answered, would improve the current situation where hardly any criticism is written or answered, and little discussion takes place. And methodological criticisms – that someone did not respond to a criticism – are much easier to evaluate than scientific criticisms.

What if a scientist gives a low quality answer instead of a non-answer? This gives a critic more to work with. He can write a followup criticism. If he does a good job, then it will get progressively harder for the scientist giving a succession of bad answers to avoid saying anything that is wrong and easy for many people to evaluate. It’s hard to keep responding to criticism, including followups, and do it badly, but avoid anything that would noticeably look bad.

And this leads into the other main issue: What if scientists get too many criticisms to address and trying to keep up with them consumes lots of time? This would be an issue for popular scientists, and it could also be an issue when an obscure project gets even just one highly persistent critic. Someone could write dozens of followup criticisms that don’t make much sense. Methods for dealing with these issues are explained in the Paths Forward articles linked earlier, and I’ll go over some main points:

There’s no need to repeat yourself. The more your response to a criticism addresses general principles, the more you can re-use it in response to future inquiries. If people bring up points repetitively, link existing answers (including answers written by other people, which you are willing to take responsibility for just as if you wrote it yourself).

If there is a pattern of error in the criticisms, respond to that pattern itself instead of to each point individually.

If you get a bunch of unique criticisms you’ve never addressed before, you should be happy, even if you suspect the quality isn’t great. You can’t know if they are true without considering what the answers to those criticisms are. It’s a good use of your time to think through new and different criticisms which don’t fall into any pattern you’re already familiar with. That is a thing you can’t have too much of, and which is hard for critics to provide. The world is not full of too many novel criticisms. The vast majority of criticisms are boring because they fit into known patterns, like fallacies, and pointing that out and linking to a text addressing the issue is cheap and easy (and if people did that regularly, it would help spread knowledge of those common fallacies and other patterns of intellectual error, to the point that eventually people would stop making those errors so much).

It’s important, with suspected bad ideas, to either address them individually or address them by connecting them to some kind of general pattern which is addressed (sometimes we criticize types or categories of ideas, e.g. there are criticisms of all ad hominem arguments as a group). Ignoring a suspected bad idea with no answer - no ability to actually say what’s bad about it – is irrational and allows for bias and ignoring important, good criticisms. There is no way to know which criticisms are correct or high quality other than answering them. Circumstantial evidence, like whether the first words of sentences are capitalized, whether it uses slang, or whether the author has over 10,000 fans, are bad ways to judge ideas. Ideas should be judged by their content, not their source.

If you get tons of attention, you ought to be able to get some of your many admiring fans to help you out by acting as your proxies and answering common criticisms for you (primarily by handing out standard links). You can give an issue personal attention when your proxies don’t know the answer. You can also hire proxies if you’re popular/important enough to have money. Getting lots of interest in your work, and having resources to deal with it, generally happen proportionally. Using proxies to speak for you is fine as long as you take responsibility for what they do – if someone does a bad job, either address the issue yourself or fire him, but don’t just let it continue and then claim to be answering criticism through your proxies.

I’m not attempting to present an exact set of rules for people to follow, nor an exact set of instructions for what people should do. Science is a creative process. It requires flexibility and individuality. These are rough guidelines which would improve the situation, not exact steps to make it perfect. These proposals would increase the quantity of discussion and offer some improved ways for interested parties to engage. It offers mechanisms for identifying and correcting errors which offer better clarity and transparency when they are violated. I think the same proposal would improve every intellectual field – philosophy, psychology, history, economics – not just science.

[1] Forums should:

These simple standards are egregiously violated by currently popular forums like Twitter, Facebook and Reddit. The violations are intentional, not a technical issue.

Note that people don’t need to run their own forums. Each project can add a new sub-forum on a site that hosts many forums. Technologically, creating thousands of mostly-silent forums can be very cheap and easy. And there can easily be tools to monitor many forums at once and be notified of new posts. This technology pretty much already exists.

From the Fallible Ideas Discord chatroom:

[1:58 PM] anonymous: i wanna eat but i’m not hungry what should i do?

[1:59 PM] anonymous: what should i do to not want to eat**

[2:01 PM] filthy_inductivist: are you bored?

[2:02 PM] anonymous: no, i’m playing a game and having fun

[2:03 PM] curi: why do you want to eat?

[2:03 PM] anonymous: idk

[2:07 PM] curi: do you want to eat any food or a specific food?

[2:07 PM] anonymous: candy

[2:07 PM] anonymous: cuz it tastes good

[2:08 PM] curi: when you are hungry, do you eat mostly candy or do you eat other things? maybe you should eat less non-candy.

[2:09 PM] anonymous: other things

[2:09 PM] curi: i suggest you make 50% of every meal candy until you don't feel like eating that much candy any more.

[2:09 PM] anonymous: wuhh?

[2:09 PM] curi: just have little portions of the other stuff

[2:09 PM] anonymous: how would that help xD

[2:09 PM] curi: and eat the candy you want

[2:10 PM] curi: you will get tired of candy after a while and not want so much

[2:10 PM] curi: or if you don't, that's ok, you should eat what you want.

[2:10 PM] anonymous: ohh

[2:11 PM] anonymous: ok i’ll try dat for a few days

I think this chat is a good example of a production discussion. It's short and to the point. I didn't need many questions to find out what was going on. I gave actionable advice that I think will actually be useful and used. I made the advice simple enough to be understood, and I also gave a brief explanation of the reasoning. And anonymous did a great job of giving short, clear, direct answers to my questions, which was really helpful. Trying it for a few days is a good idea too – it's worth a try but if they already thought it was a great idea, rather than just something to try, that would be suspicious that they were overestimating how well they understood it.

If none of your discussions look like this, that's a sign something is going wrong. Some can be longer and involve more misunderstandings, but some should be short and successful.

Context: I recently have been playing Vindictus with internetrules.

curi:

https://www.reddit.com/r/Vindictus/comments/a08v6u/game_akin_to_vindicus/

do you know any of the games suggested in comments there?

internetrules:

no. one game that i thought was kind of like playing vella specifically, is metal gear rising revengeance

curi:

o ya i think i saw a vid of that game b4. looks like a too-easy single player game meant to make you feel powerful was my impression.

internetrules:

yeah that seems about right, in harder modes i think its alot harder tho

curi:

i’d be surprised if it was actually very hard

i find single player games normally way too easy even if they have 4 difficulty modes and u use hardest

internetrules:

i remember playing it 3 years ago and getting really stuck on some boss fights on the second highest difficulty. i cant really tell exactly how hard it was tho cuz i think i was probably really bad at games back then

curi:

sometimes they are hard if you’re playing on console and the controls suck … if you count that

internetrules:

it also has like 1 move which your are suppose to use like 50% of the time called offensive defence, its kind of like a dodge with maybe a second of invuln.

it was a move pretty ez to use and abuse

curi:

i played assassin’s creed odyssey on my PC with xbox controller – it was totally designed for controller, not keyboard/mouse, and i think that worked better in general. and seriously 2 of the hardest parts of combat were

1) some awful button mappings u can’t change

2) some glitches where ur move doesn’t hit, i think cuz wolves and certain other animals have broken hitboxes

u get 8 abilities but only 4 at a time and there is a swap button. and the swap button is really really hard to hit during combat. it’s dpad down (while also holding left trigger). you have to either stop moving or use your right hand (which is what i usually did)

it’s really disruptive to gameplay to be trying to hit dpad down with ur right hand while running backwards and hoping nothing attacks u cuz u can’t hit dodge button cuz u moved ur right hand

and ur moving ur hand around to different places while trying to still hit the right buttons

it’s like taking ur hand off the keyboard and back on repeatedly and trying never to typo

always put it back in the right place

also dpads on modern controllers have horrible design

so u often hit the wrong direction b/c it’s not 4 separate buttons

so it’s not really suitable for in-combat use b/c of shitty button quality

i think the xbox one is even worse than the switch pro controller one

u try to hit down but u get left or right a fair amount

so then, pretty often, u switch melee weapons when u wanted to swap abilities

so u get fucked over

so yeah THAT was the hard part

also really hard was changing arrow types

that was on dpad left. even further away

and you have to toggle it multiple times

and you have to watch ur arrow thing to see when u toggle to the ones u want

cuz it’s just going thru a list in order

so u have to look away from combat and hit the like worst button on the controller some specific number of times

and if u hit an extra time u get to keep going to cycle back to the one u want

internetrules:

I really like the dpad on the steam controller, it’s basically just 1 sensor that sees where your pressing, and then it can also feel when you push into it

File Transfer: 56487136803__3AA370CD-DC84-4B56-AD8D-F8A0E4F439CF.jpeg

i guess the joystick could be considerd the dpad as well, it depends how you bind it, theres alot of customization for the controller

curi:

no joystick = dstick

dpad specifically means not the stick, the pad, where it’s just 4 directional buttons + diagonals. like original nintendo

except that xbox and switch dpads today are much worse build than original nintendo one

they should just give u 4 small buttons, that is way better

that’s what joycon have

it’s so much better

even if the buttons didn’t suck the assassin’s creed controls would still be terrible tho

b/c seriously how are you supposed to press stuff below ur left thumb during combat? stop using dstick or move right hand? both options suck

it’s so easy to fix

u hold left trigger to bring up the abilities

just let u double tap it to swap abilities

there are lots of other options but yeah the developers are idiots

i literally just didn’t use half my abilities unless it was one of the hardest fights

wasn’t worth the trouble

and the only reason i swapped arrows was for the non-lethal ones. the special arrows for doing dmg were not worth the hassle

and it got super easy after a while on hardest mode

internetrules:

how could they fuck up the controlls that much? dont they have like play testers and stuff?

curi:

in short, play testing in the industry is a really bad job where you waste your time

and its mostly used to fix some of the worst bugs

and to try to make up for hiring bad programmers

they basically don’t trust play testers with design decisions or balance

and the higher level ppl in charge of that stuff are idiots in most companies / for most games

like way way way worse than jeff kaplan

who really isn’t that good at balance stuff (actually he’s not in charge of it, but there is someone who is)

there are some special end game bosses

a cyclops and a minotaur

but u can kill them by staying away and shooting arrows

super ez and stupid

and u can basically spam short dodges with no stamina limit and be invincible over 80% of the time

and if any of the dodges happen to actually dodge an attack, u get several seconds of slow motion to counter attack in

during which i think you’re invincible too

internetrules:

how are the people in charge of playtesting idiots?

curi:

the balance and design ppl are bad at games

they are casual newbies who probably don’t see the problem with standing still to swap abilities during combat

cuz they are playing on normal and take no dmg anyway

they are like “well i was just using 4 abilities, that is plenty for me, but if ur an advanced player u can swap, so that seems fine”

they don’t realize shit like u have to either repeat ur heal in both sets of 4 (losign a slot) or else u have to be able to switch back really fast

cuz ur heal is fuckign important

it heals u like 60% in a game where a lot of stuff will hit u for 30% of ur life

internetrules:

and do most of the people playing the game not notice cuz they are casual as well?

curi:

and as far as playtesting basically the programmers do this:

they write a stupid bug

they don’t notice or test what they wrote themselves

some playtester has to try their code and see it doesn’t work

then they write a quick thoughtless fix and don’t check if it works

and send it back to the playtesters

and sometimes they will keep failing to fix something a dozen times

and make the playtesters check if their fix worked every time

and never check it themselves or figure out wtf they are doing

they just keep trying something and hope it works, and let playtester check it

and sometimes they forget to change anything at all and playtesters still test it again

that happens too

or they spend all day on reddit

but want to pretend to work

so they mark it as they tried to fix it instead of telling their boss they didn’t get to it this week and being asked to come in on saturday

so then the playtester has to test it again cuz the lazy guy lied

or they do shit like

there are 10 bugs

they go thru and fix some

then mark them all done

cuz like, they tried, and they wanna be done now

so some get playtested again with no fix

ppl are like that

the playtesters are low paid and are not valued

no1 cares about wasting their time

no1 thinks they have brains

everyone is like “well they are getting paid to play video games, so lucky”

but they are just repeating boring crap a lot cuz they have bad tools to go straight to the right part to test it

so it takes way too long

and then there are the intermittent issues

where no one knows exactly how to make the bug happen

so sometimes they just have to play for hours, cuz sometimes you get it after 10min and sometimes 6 hours and sometimes 3 days.

the rarer the bug, the worse it is, the harder to fix

so now imagine the process i was talking about where they keep not fixing it and being lazy and shit

or putting in some code they HOPE will work but didn’t test, and let playtester test it

but with a bug that has a 10% chance to show up per hour you play

so you could play all day, not see it, and have to do it again tomorrow cuz it could easily not be fixed

and you end up having to test and report that bug 10 times before it gets fixed

so you spend 2 weeks on it

that one stupid bug

except it’s not 2 weeks in a row, it’s spread out over time more b/c you keep having to wait for the fixes

programmers often need a few days per fix, even tho they only spend 30min on it, b/c they have other things to do too

so everyone is always task switching. the programmers have 50 bugs to fix and the playtesters have 50 bugs to test

so ppl keep switching what they are working on and forgetting things

which makes everything take MORE total time cuz it’s less effective/effficient, and it spreads things out over time more

so if you spend 2 weeks on a bug, it could be over a period of 3 months

or more

you see hints about how this works with OW

where a bug is put on PTR

and ppl notice it day 1

and wonder how the playtesters missed it

and half they time they DIDNT

they reported it

it just takes months to fix

which is why blizz then releases the PTR to live with the bug still in if it isn’t a MAJOR bug

and then fixes it in the next patch a month after the first PTR goes live, 2 months after the playerbase saw the bug, 3 months after internal testers already reported it

oh and the worst part

ppl re-break things

or break other things that aren’t what they were trying to change

so you get some bug fixed, finally, and then later someone is changing something else and his code effects it and it breaks again

b/c the programmers don’t even know what the code they just wrote will do TO THE WHOLE GAME – it could fuck up some random thing somewhere b/c the code isn’t very well isolated/separated – then basically they are constantly making playtesters replay the whole game to see if anything broke

and the playtesters are bored as fuck and not paying attention and just go through the motions and test specific things on a list they are told to test + play thru the main story and see if something breaks like a quest won’t complete or they get stuck somehow

or some other obvious big issue

ppl are bad at things. it’s not just video game dev. it’s basically almost everyone is bad at almost everything, that’s how the world works. this is not really some horror story compared to other industries. my sister works in fashion and like talks with factories in china and tries to get clothes produced. i don’t really know anything about it but i can just predict, on general principles, that there are huge, ridiculous inefficiencies there too

and ppl being bad at stuff is is why assassin’s creed is super trivally easy on normal mode and easy on nightmare.

internetrules:

and so most programmers are bad, and cause a ton of bugs? how much of a demand is there for actually good programmers? do people realize most programmers are bad?

curi:

they tried to make diablo 3 hard on max difficulty btw

that was interesting

they promised it’d be super hard

they said they playtested it, did their best to make it as hard as they could beat

then doubled the hp and dmg of the enemies

so it’d be harder than their own skill level

and on launch it was actually hard. i liked it. fun game. i didn’t think it was as hard as it was supposed to be, but i liked it.

the playerbase complaiend so much that 10 nerf patches later the game was boring and easy

50% of players think they should be playing the hardest stuff that blizz said was for the top 2% of players

and they try it, die, and then complain

cuz they want to think they are good

so blizz has to make the hardest mode easy so everyone can think they are good

assassin’s creed is the same issue

if the hardest mode was hard, lots of ppl would play it, die, and feel bad and get mad

so you can’t put in a hard mode. it cannot exist.

the game company cannot admit there is anyone better than the guy who sucks but beats “hard” mod

there are far more arrogant ppl than skilled ppl to sell to

and so most programmers are bad, and cause a ton of bugs? how much of a demand is there for actually good programmers? do people realize most programmers are bad?

yeah this is well known, it’s why google is paying $300k/year USD or more to thousands of programmers

b/c there are not enuf good programmers and u have to pay a ton to get some

it’s competitive to get them

but the game dev industry decided instead of trying to pay salaries to compete with google, mostly they will just underpay ppl who want to make games

so they get a lot of ppl fresh out of college and they have high turnover, ppl give up and leave

internetrules:

i was talking to a guy in general chat in OW [Overwatch] who was bronze and always blamed his team and matchmaking for him losing, i guess thats the kind of guy who would complain at not being able to finish the hardest difficulty

curi:

him and another half of hte population

it’s so many ppl

in general games are actually easy software to make

and are mostly copying the same crap as the last game

so it’s well known how to do it

they aren’t designing any new code that wasn’t in some other game

and they buy the physics engine and the 3d graphics code and shit

they don’t even write that

they just use unity or havoc or whatever

internetrules:

and then you have traditions in making games, which means the game wont be super terrible, and it will actually be marketable?

curi:

and then they have software devs who can’t even write decent pathfinding

pathfinding with A* is trivial enough to be like a homework assignment for a college freshman.

and then you get game releases like Pillars of Eternity that can’t fucking do it

and the enemies can barely move

and i’m not joking

guy glitched an end boss on a pillar and shot it to death

just a pillar. no walls on either side

but it couldn’t move directly forward and got stuck

meanwhile in my own game some enemies got stuck trying to go up a narrow path and none of htem would go a small distance around where there was plenty of open space

so they are all just running into each other at a tiny chokepoint instead of going around

and i just mass aoe spell them

and then think to myself

this is stupid, i could have written better AI than this when i was in high school

cuz i guess unity didn’t come with pathfinding included

so they never got it to work decently?

and so some of the fights that are supposed to be hard are actually a joke

internetrules:

i remember you talking about a game where the max party size is 6, and a guy beat the game with just 1 person on hardest difficulty, do you know what game that was?

curi:

the balance scaling in that game was awful too

on max difficulty it starts out hard at the beginning, esp while ur learning

and stuff has a ton of hp, dies slow

but at later levels everything was dying so fast i couldn’t really even play with my spells – like low level vindictus today with all ur gear on – that i didn’t finish the game

there are mods for the game made by players. it’s somewhat moddable. so i looked into it and no1 ever made a “give enemies 5x the hp mod”. everyone is so bad they didn’t care? idk

the sequel had a mod to give more enemy hp

but it was only like 50% more hp or something, you couldn’t just type in a number

soloing a 6man party RPG is a LOT of games

that’s common

internetrules:

oh

curi:

the only thing making it less common is that a lot more party RPGs, especially recent ones, are 4 characters max instead of 6

just like by default you can solo party RPG games more than 50% of the time

on hardest mode

it tends to just work

in majority of games

also in a ton of games it gets EASIER once you level up some

and the start is actually the hardest part when u do that

internetrules:

i remember you talking about how people who like the game the most, have the easiest time, cuz they do side quests, then main story gets easier cuz higher level

curi:

usually the AI is super bad so u can lure enemies 1 at a time

or peak a corner, shoot htem, hide, repeat

stuff like that

also required bosses are usually not super hard b/c they don’t want ppl to get stuck

yes!

the GOOD players tend to play more, do more stuff = get more powerful items, more levels, etc = have easier time while being more skilled

sux

internetrules:

im pretty sure that was a problem a ton of people were complaining about with the first southpark game

which if even the casuals complain about it, then its prob waaaay to easy

curi:

that game had shitty combat

the point was the south park stuff

jokes, dialog, etc

combat was mario rpg style which is boring

but ya i did max difficulty and beat it in one day np and if i had done more sidequests it’d just have been easier

but i enjoyed the game

cuz i didn’t have the mindset of it being about combat or skill

i just saw it as kinda like watching south park tv show…

what happened with diablo 3 is instructive

the general complaining resulted in everything being easier

but it’s not just that

also specifically everything that killed ppl got complaints

whatever ppl were dying to, they called unfair

internetrules:

i remember when i was playing that game that it was kinda hard cuz the mouse i was using while playing it, had its like rightclick button really fucked up or something, so i couldnt use it to like take less damage when people attacked me or something

curi:

so all the hardest things got super extra nerfed so they would be “fair” meaning ppl don’t die to it much

so every difficulty spike got removed from the game

so there was nothing scary in the game anymore

nothing where ur like “oh shit, i gotta be careful with that”

they removed everything that requires changing ur strategy, being defensive, playing safe, etc

like damage reflect is a good example

it was one of the random modifiers that elites could have

they’d roll a few random things

internetrules:

did older games do a better job at difficulty? alot of people talk about how old games were really hard. like Xcom and old school plat formers

curi:

and damage reflect was one of the most deadly

it’d turn on and off

and if u attack during reflect u take like 10% of the dmg u dealt

which is a ton, enemies have more hp than players

so ppl were constantly killing themselves

b/c they didn’t check mods b4 attacking, or didn’t pay attention to if reflect was active

or didn’t attack a little then heal then a little more

they just do burst dmg carelessly

so they had to nerf the fuck out of that so it wouldn’t be dangerous anymore

a lot of older games were harder but also ppl were worse at games then

some old games used difficulty to make up for shortness

they could fit way less art on a disk, had worse programming tools, worse computers, etc, so games then were often way shorter and smaller

so they’d make it hard so u don’t finish too fast

or so u spend more quarters in arcade

but also the gamer audience in the past was early adopters

ppl who care about computers and stuff

nerds

so the avg player was a lot better, more patient, etc

now it’s more mainstream and the random idiots have a lot more money than the tech ppl

b/c there are way more of them

and if you think shit like diablo 3 or assassin’s creed is bad

it has NOTHING on farmville and candy crush

which are what girls play

who could not play assassin’s creed on easy

who would be hard stuck bronze in OW

and those games are HUGE and bring in a ton of money

it’s also what older ppl play

like my parents could not play diablo 3 no matter how ez it is

but they could candy crush

so the REAL mainstream is shit like candy crush

assassins’ creed is just mainstream OF GAMERS

who are 95% male

and 90% under 40

(i made up the stats but u get the idea)

and who have played games for hundreds of hours before

the mainstream of society is 52% women, a lot of old ppl and a lot of little kids who suck at games b/c they get 1 hour of screen time per week (and esp the little girls are commonly AWFUL cuz they get NO HELP to stop sucking, whereas the little boys will get help from their friends or even parents or other resources to learn to play) … and so on … and they make candy crush and farmville ppl rich and would have a hard time playing any game you or I would even consider

mobile gaming is huge b/c ppl have 5 or 10 minutes to waste here or there, it’s not really even similar to what you think gaming is, or even what xbox players think gaming is.

internetrules:

it seems like turn based games could work as mobile

as like actual hard games that you could play

curi:

ppl are impatient and don’t want to strategize, which they find even harder than hitting buttons in real time games

strategy THINKING would be the WORST thing u could put in a game if u want it to be mainstream

that’s probably why the ipad boardgame-like turn based battle games i liked (like battle of the bulge) went out of business

internetrules:

how about for a game that skilled players like in a mobile form?

curi:

there are niche games – ones aimed at smaller groups – but even those are generally too easy for me b/c i’m too much of an outlier

like with boardgames, i’m a really strong chess player so i tend to be way too good at boardgames compared to other ppl

cuz skill carries over

and it’s similar with lots of turn based strategy stuff

and the AIs to play with are always so shitty

even tho the knowledge of how to make much much better AIs exists. it’s available. but game companies basically never seem to do it

is it ok with you if i post this conversation online?

i’ll put your name as internetrulez? how should i spell it?

internetrules:

anything is fine for my name

execpt [my real name]

curi:

ok but tell me spelling

internetrules:

internetrules no caps

curi:

k

i got in a big argument the other day with a guy who didn’t understand not capitalizing all internet names >>

he was like u always capitalize proper nouns

like the iPhone????????

internetrules:

i remember that in discord

curi:

ya