Gyrodiot wrote at the Less Wrong Slack Philosophy chatroom:

I was waiting for an appropriate moment to discuss epistemology. I think I understood something about curi's reasoning about induction After reading a good chunk of the FI website. Basically, it starts from this:

He quotes from: http://fallibleideas.com/objective-truth

There is an objective truth. It's one truth that's the same for all people. This is the common sense view. It means there is one answer per question.

The definition of truth here is not the same as The Simple Truth as described in LW. Here, the important part is:

Relativism provides an argument that the context is important, but no argument that the truth can change if we keep the context constant.

If you fixate the context around a statement, then the statement ought to have an objective truth value

Yeah. (The Simple Truth essay link.)

In LW terms that's equivalent to "reality has states and you don't change the territory by thinking differently about the map"

Yeah.

From that, FI posits the existence of universal truths that aren't dependent on context, like the laws of physics.

More broadly, many ideas apply to many contexts (even without being universal). This is very important. DD calls this "reach" in BoI (how many contexts does an idea reach to?), I sometimes go with "generality" or "broader applicability".

The ability for the same knowledge to solve multiple problems is crucial to our ability to deal with the world, and for helping with objectivity, and for some other things. It's what enabled humans to even exist – biological evolution created knowledge to solve some problems related to survival and mating, and that knowledge had reach which lets us be intelligent, do philosophy, build skyscrapers, etc. Even animals like cats couldn't exist, like they do today, without reach – they have things like behavioral algorithms which work well in more than one situation, rather than having to specify different behavior for every single situation.

The problem with induction, with this view is that you're taking truths about some contexts to apply them to other contexts and derive truths about them, which is complete nonsense when you put it like that

Some truths do apply to multiple contexts. But some don't. You shouldn't just assume they do – you need to critically consider the matter (which isn't induction).

From a Bayesian perspective you're just computing probabilities, updating your map, you're not trying to attain perfect truth

Infinitely many patterns both do and don't apply to other contexts (such as patterns that worked in some past time range applying tomorrow). So you can't just generalize patterns to the future (or to other contexts more generally) and expect that to work, ala induction. You have to think about which patterns to pay attention to and care about, and which of those patterns will hold in what ranges of contexts, and why, and use critical arguments to improve your understanding of all this.

We do [live in our own map], which is why this mode of thought with absolute truth isn't practical at all

Can you give an example of some practical situation you don't understand how to address with FI thinking, and I'll tell you how or concede? And after we go through a few examples, perhaps you'll better understand how it works and agree with me.

So, if induction is out of the way, the other means to know truth may be by deduction, building on truth we know to create more. Except that leads to infinite regress, because you need a foundation

CR's view is induction is not replaced with more deduction. It's replaced with evolution – guesses and criticism.

So the best we can do is generate new ideas, and put them through empirical test, removing what is false as it gets contradicted

And we can use non-empirical criticism.

But contradicted by what? Universal truths! The thing is, universal truths are used as a tool to test what is true or false in any context since they don't depend on context

Not just contradicted by universal truths, but contradicted by any of our knowledge (lots of which has some significant but non-universal reach). If an idea contradicts some of our knowledge, it should say why that knowledge is mistaken – there's a challenge there. See also my "library of criticism" concept in Yes or No Philosophy (discussed below) which, in short, says that we build up a set of known criticisms that have some multi-context applicability, and then whenever we try to invent a new idea we should check it against this existing library of known criticisms. It needs to either not be contradicted by any of the criticisms or include a counter-argument.

But they are so general that you can't generate new idea from them easily

The LW view would completely disagree with that: laws of physics are statements like every other, they are solid because they map to observation and have predictive power

CR says to judge ideas by criticism. Failure to map to observation and lack of predictive power are types of criticism (absolutely not the only ones), which apply in some important range of contexts (not all contexts – some ideas are non-empirical).

Prediction is great and valuable but, despite being great, it's also overrated. See chapter 1 of The Fabric of Reality by David Deutsch and the discussion of the predictive oracle and instrumentalism.

http://www.daviddeutsch.org.uk/books/the-fabric-of-reality/excerpt/

Also you can use them to explain stuff (reductionism) and generate new ideas (bottom-up scientific research)

From FI:

When we consider a new idea, the main question should be: "Do you (or anyone else) see anything wrong with it? And do you (or anyone else) have a better idea?" If the answers are 'no'and 'no' then we can accept it as our best idea for now.

The problem is that by having a "pool of statements from which falsehoods are gradually removed" you also build a best candidate for truth. Which is not, at all, how the Bayesian view works.

FI suggests evolution is a reliable way to suggest new ideas. It ties well into the framework of "generate by increments and select by truth-value"

It also highlights how humans are universal knowledge machines, that anything (in particular, an AGI) created by a human would have knowledge than humans can attain too

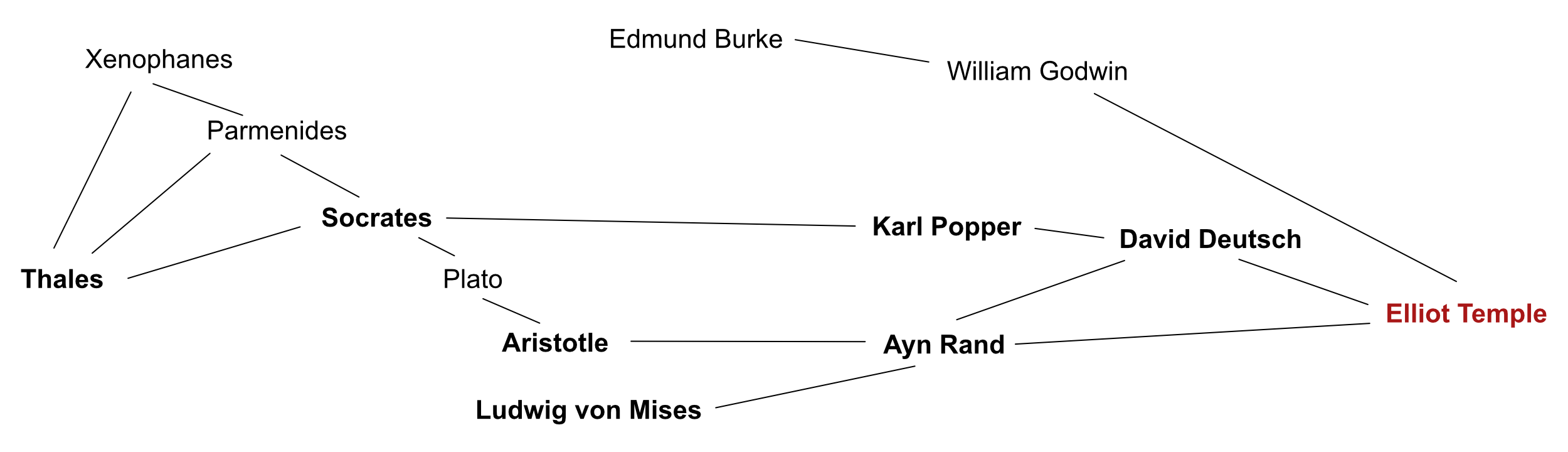

Humans as universal knowledge creators is an idea of my colleague David Deutsch which is discussed in his book, The Beginning of Infinity (BoI).

http://beginningofinfinity.com

But that's not an operational definition : if an AGI creates knowledge much faster than any human, they won't ever catch up and the point is moot

Yes, AGI could be faster. But, given the universality argument, AGI's won't be more rational and won't be capable of modes of reasoning that humans can't do.

The value of faster is questionable. I think no humans currently maximally use their computational power. So adding more wouldn't necessarily help if people don't want to use it. And an AGI would be capable of all the same human flaws like irrationalities, anti-rational memes (see BoI), dumb emotions, being bored, being lazy, etc.

I think the primary cause of these flaws, in short, is authoritarian educational methods which try to teach the kid existing knowledge rather than facilitate error correction. I don't think an AGI would automatically be anything like a rational adult. It'd have to think about things and engage with existing knowledge traditions, and perhaps even educators. Thinking faster (but not better) won't save it from picking up lots of bad ideas just like new humans do.

That sums up the basics, I think The Paths Forwards thing is another matter... and it is very, very demanding

Yes, but I think it's basically what effective truth-seeking requires. I think most truth-seeking people do is not very effective, and the flaws can actually be pointed out as not meeting Paths Forward (PF) standards.

There's an objective truth about what it takes to make progress. And separate truths depending on how effectively you want to make progress. FI and PF talk about what it takes to make a lot of progress and be highly effective. You can fudge a lot of things and still, maybe, make some progress instead of going backwards.

If you just wanna make a few tiny contributions which are 80% likely to be false, maybe you don't need Paths Forward. And some progress gets made that way – a bunch of mediocre people do a bunch of small things, and the bulk of it is wrong, but they have some ability to detect errors so they end up figuring out which are the good ideas with enough accuracy to slowly inch forwards. But, meanwhile, I think a ton of progress comes from a few great (wo)men who have higher standards and better methods. (For more arguments about the importance of a few great men, I particularly recommend Objectivism. E.g. Roark discusses this in his courtroom speech at the end of The Fountainhead.)

Also, FYI, Paths Forward allows you to say you're not interested in something. It's just, if you don't put the work into knowing something, don't claim that you did. Also you should keep your interests themselves open to criticism and error correction. Don't be an AGI researcher who is "not interested in philosophy" and won't listen to arguments about why philosophy is relevant to your work. More generally, it's OK to cut off a discussion with a meta comment (e.g. "not interested" or "that is off topic" or "I think it'd be a better use of my time to do this other thing...") as long as the meta level is itself open to error correction and has Paths Forward.

Oh also, btw, the demandingness of Paths Forward lowers the resource requirements for doing it, in a way. If you're interested in what someone is saying, you can be lenient and put in a lot of effort. But if you think it's bad, then you can be more demanding – so things only continue if they meet the high standards of PF. This is win/win for you. Either you get rid of the idiots with minimal effort, or else they actually start meeting high standards of discussion (so they aren't idiots, and they're worth discussing with). And note that, crucially, things still turn out OK even if you misjudge who is an idiot or who is badly mistaken – b/c if you misjudge them all you do is invest less resources initially but you don't block finding out what they know. You still offer a Path Forward (specifically that they meet some high discussion standards) and if they're actually good and have a good point, then they can go ahead and say it with a permalink, in public, with all quotes being sourced and accurate, etc. (I particularly like asking for simple things which are easy to judge objectively like those, but there are other harder things you can reasonably ask for, which I think you picked up on in some ways your judgement of PF as demanding. Like you can ask people to address a reference that you take responsibility for.)

BTW I find that merely asking people to format email quoting correctly is enough barrier to entry to keep most idiots out of the FI forum. (Forum culture is important too.) I like this type of gating because, contrary to moderators making arbitrary/subjective/debatable judgements about things like discussion quality, it's a very objective issue. Anyone who cares to post can post correctly and say any ideas they want. And it lacks the unpredictability of moderation (it can be hard to guess what moderators won't like). This doesn't filter on ideas, just on being willing to put in a bit of effort for something that is productive and useful anyway – proper use of nested quoting improves discussions and is worth doing and is something all the regulars actively want to do. (And btw if someone really wants to discuss without dealing with formatting they can use e.g. my blog comments which are unmoderated and don't expect email quoting, so there are still other options.)

It is written very clearly, and also wants to make me scream inside

Why does it make you want to scream?

Is it related to moral judgement? I'm an Objectivist in addition to a Critical Rationalist. Ayn Rand wrote in The Virtue of Selfishness, ch8, How Does One Lead a Rational Life in an Irrational Society?, the first paragraph:

I will confine my answer to a single, fundamental aspect of this question. I will name only one principle, the opposite of the idea which is so prevalent today and which is responsible for the spread of evil in the world. That principle is: One must never fail to pronounce moral judgment.

There's a lot of reasoning for this which goes beyond the one essay. At present, I'm just raising it as a possible area of disagreement.

There are also reasons about objective truth (which are part of both CR and Objectivism, rather than only Objectivism).

The issue isn't just moral judgement but also what Objectivism calls "sanction": I'm unwilling to say things like "It's ok if you don't do Paths Forward, you're only human, I forgive you." My refusal to actively do anti-judgement stuff, and approve of PF alternatives, is maybe more important than any negative judgements I've made, implied or stated.

It hits all the right notes motivation-wise, and a very high number of Rationality Virtues. Curiosity, check. Relinquishment, check. Lightness, check. Argument, triple-check.

Yudkowsky writes about rational virtues:

The fifth virtue is argument. Those who wish to fail must first prevent their friends from helping them.

Haha, yeah, no wonder a triple check on that one :)

Simplicity, check. Perfectionism, check. Precision, check. Scholarship, check. Evenness, humility, precision, Void... nope nope nope PF is much harsher than needed when presented with negative evidence, treating them as irreparable flaws (that's for evenness)

They are not treated as irreparable – you can try to create a variant idea which has the flaw fixed. Sometimes you will succeed at this pretty easily, sometimes it’s hard but you manage it, and sometimes you decide to give up on fixing an idea and try another approach. You don’t know in advance how fixable ideas are (you can’t predict the future growth of knowledge) – you have to actually try to create a correct variant idea to see how doable that is.

Some mistakes are quite easy and fast to fix – and it’s good to actually fix those, not just assume they don’t matter much. You can’t reliably predict mistake fixability in advance of fixing it. Also the fixed idea is better and this sometimes helps leads to new progress, and you can’t predict in advance how helpful that will be. If you fix a bunch of “small” mistakes, you have a different idea now and a new problem situation. That’s better (to some unknown degree) for building on, and there’s basically no reason not to do this. The benefit of fixing mistakes in general, while unpredictable, seems to be roughly proportional to the effort (if it’s hard to fix, then it’s more important, so fixing it has more value). Typically, the small mistakes are a small effort to fix, so they’re still cost-effective to fix.

That fixing mistakes creates a better situation fits with Yudkowsky’s virtue of perfectionism.

(If you think you know how to fix a mistake but it’d be too resource expensive and unimportant, what you can do instead is change the problem. Say “You know what, we don’t need to solve that with infinite precision. Let’s just define the problem we’re solving as being to get this right within +/- 10%. Then the idea we already have is a correct solution with no additional effort. And solving this easier problem is good enough for our goal. If no one has any criticism of that, then we’ll proceed with it...")

Sometimes I talk about variant ideas as new ideas (so the original is refuted, but the new one is separate) rather than as modifying and rescuing a previous idea. This is a terminology and perspective issue – “modifying" and “creating" are actually basically the same thing with different emphasis. Regardless of terminology, substantively, some criticized flaws in ideas are repairable via either modifying or creating to get a variant idea with the same main points but without the flaw.

PF expects to have errors all other the place and act to correct them, but places a burden on everyone else that doesn't (that's for humility)

Is saying people should be rational burdensome and unhumble?

According to Yudkowsky's essay on rational virtues, the point of humility is to take concrete steps to deal with your own fallibility. That is the main point of PF!

PF shifts from True to False by sorting everything through contexts in a discrete way.

The binary (true or false) viewpoint is my main modification to Popper and Deutsch. They both have elements of it mixed in, but I make it comprehensive and emphasized. I consider this modification to improve Critical Rationalism (CR) according to CR's own framework. It's a reform within the tradition rather than a rival view. I think it fits the goals and intentions of CR, while fixing some problems.

I made educational material (6 hours of video, 75 pages of writing) explaining this stuff which I sell for $400. Info here:

https://yesornophilosophy.com

I also have many relevant, free blog posts gathered at:

http://curi.us/1595-rationally-resolving-conflicts-of-ideas

Gyrodiot, since I appreciated the thought you put into FI and PF, I'll make you an offer to facilitate further discussion:

If you'd like to come discuss Yes or No Philosophy at the FI forum, and you want to understand more about my thinking, I will give you a 90% discount code for Yes or No Philosophy. Email [email protected] if interested.

Incertitude is lack of knowledge, which is problematic (that's for precision)

The clarity/precision/certitude you need is dependent on the problem (or the context if you don’t bundle all of the context into the problem). What is your goal and what are the appropriate standards for achieving that goal? Good enough may be good enough, depending on what you’re doing.

Extra precision (or something else) is generally bad b/c it takes extra work for no benefit.

Frequently, things like lack of clarity are bad and ruin problem solving (cuz e.g. it’s ambiguous whether the solution means to take action X or action Y). But some limited lack of clarity, lower precision, hesitation, whatever, can be fine if it’s restricted to some bounded areas that don’t need to be better for solving this particular problem.

Also, about the precision virtue, Yudkowsky writes,

The tenth virtue is precision. One comes and says: The quantity is between 1 and 100. Another says: the quantity is between 40 and 50. If the quantity is 42 they are both correct, but the second prediction was more useful and exposed itself to a stricter test.

FI/PF has no issue with this. You can specify required precision (e.g. within plus or minus ten) in the problem. Or you can find you have multiple correct solutions, and then consider some more ambitious problems to help you differentiate between them. (See the decision chart stuff in Yes or No Philosophy.)

PF posits time and again that "if you're not achieving your goals, well first that's because you're not faillibilist". Which is... quite too meta-level a claim (that's for the Void)

Please don't put non-quotes in quote marks. The word "goal" isn't even in the main PF essay.

I'll offer you a kinda similar but different claim: there's no need to be stuck and not make progress in life. That's unnecessary, tragic, and avoidable. Knowing about fallibilism, PF, and some other already-known things is adequate that you don't have to be stuck. That doesn't mean you will achieve any particular goal in any particular timeframe. But what you can do is have a good life: keep learning things, making progress, achieving some goals, acting on non-refuted ideas. And there's no need to suffer.

For more on these topics, see the FI discussion of coercion and the BoI view on unbounded progress:

http://beginningofinfinity.com

(David Deutsch, author of BoI, is a Popperian and is a founder of Taking Children Seriously (TCS), a parenting/education philosophy created by applying Critical Rationalism and which is where the the ideas about coercion come from. I developed the specific method of creating a succession of meta problems to help formalize and clarify some TCS ideas.)

I don't see how PF violates the void virtue (aspects of which, btw, relate to Popper's comments on Who Should Rule? cuz part of what Yudkowsky is saying in that section is don't enshrine some criteria of rationality to rule. My perspective is, instead of enshrining a ruler or ruling idea, the most primary thing is error correction itself. Yudkowsky says something that sorta sounds like you need to care about the truth instead of your current conception of the truth – which happily does help keep it possible to correct errors in your current conception.)

(this last line is awkward. The rationalist view may consider that rationalists should win, but not winning isn't necessarily a failure of rationality)

That depends on what you mean by winning. I'm guessing I agree with it the way you mean it. I agree that all kinds of bad things can happen to you, and stuff can go wrong in your life, without it necessarily being your fault.

(this needs unpacking the definition of winning and I'm digging myself deeper I should stop)

Why should you stop?

Justin Mallone replied to Gyrodiot:

hey gyrodiot feel free to join Fallible Ideas list and post your thoughts on PF. also, could i have your permission to share your thoughts with Elliot? (I can delete what other ppl said). note that I imagine elliot would want to reply publicly so keep that in mind.

Gyrodiot replied:

@JUSTINCEO You can share my words (only mine) if you want, with this addition: I'm positive I didn't do justice to FI (particularly in the last part, which isn't clear at all). I'll be happy to read Elliot's comments on this and update in consequence, but I'm not sure I will take time to answer further.

I find we are motivated by the same "burning desire to know" (sounds very corny) and disagree strongly about method. I find, personally, the LW "school" more practically useful, strikes a good balance for me between rigor, ease of use, and ability to coordinate around.

Gyrodiot, I hope you'll reconsider and reply in blog comments, on FI, or on Less Wrong's forum. Also note: if Paths Forward is correct, then the LW way does not work well. Isn't that risk of error worth some serious attention? Plus isn't it fun to take some time to seriously understand a rival philosophy which you see some rational merit in, and see what you can learn from it (even if you end up disagreeing, you could still take away some parts)?

For those interested, here are more sources on the rationality virtues. I think they're interesting and mostly good:

https://wiki.lesswrong.com/wiki/Virtues_of_rationality

https://alexvermeer.com/the-twelve-virtues-of-rationality/

http://madmikesamerica.com/2011/05/the-twelve-virtues-of-rationality/

That last one says, of Evenness:

With the previous three in mind, we must all be cautious about our demands.

Maybe. Depends on how "cautious" would be clarified with more precision. This could be interpreted to mean something I agree with, but also there are a lot of ways to interpret it that I disagree with.

I also think Occam's Razor (mentioned in that last link, not explicitly in the Yudkowsky essay), while having some significant correctness to it, is overrated and is open to specifications of details that I disagree with.

And I disagree with the "burden of proof" idea (I cover this in Yes or No Philosophy) which Yudkowsky mentions in Evenness.

The biggest disagreement is empiricism. (See the criticism of that in BoI, and FoR ch1. You may have picked up on this disagreement already from the CR stuff.)