These are replies to Ed Powell discussing IQ. This follows up on my previous post.

I believe I understand that you’re fed up with various bad counter-arguments about IQ, and why, and I sympathize with that. I think we can have a friendly and productive discussion, if you’re interested, and if you either already have sophisticated knowledge of the field or you’re willing to learn some of it (and if, perhaps as an additional qualification, you have an IQ over 130). As I emphasized, I think we have some major points of agreement on these issues, including rejecting some PC beliefs. I’m not going to smear you as a racist!

Each of these assertions is contrary to the data.

My claims are contrary to certain interpretations of the data, which is different than contradicting the data itself. I’m contradicting some people regarding some of their arguments, but that’s different than contradicting facts.

Just look around at the people you know: some are a lot smarter than others, some are average smart, and some are utter morons.

I agree. I disagree about the details of the underlying mechanism. I don’t think smart vs. moron is due to a single underlying thing. I think it’s due to multiple underlying things.

This also explains reversion to the mean

Reversion to the mean can also be explained by smarter parents not being much better parents in some crucial ways. (And dumber parents not being much worse parents in some crucial ways.)

Every piece of "circumstantial evidence" points to genes

No piece of evidence that fails to contradict my position can point to genes over my position.

assertion that there exists a thing called g

A quote about g:

To summarize ... the case for g rests on a statistical technique, factor analysis, which works solely on correlations between tests. Factor analysis is handy for summarizing data, but can't tell us where the correlations came from; it always says that there is a general factor whenever there are only positive correlations. The appearance of g is a trivial reflection of that correlation structure. A clear example, known since 1916, shows that factor analysis can give the appearance of a general factor when there are actually many thousands of completely independent and equally strong causes at work. Heritability doesn't distinguish these alternatives either. Exploratory factor analysis being no good at discovering causal structure, it provides no support for the reality of g.

Back to quoting Ed:

I just read an article the other day where researchers have identified a large number of genes thought to influence intelligence.

I’ve read many primary source articles. That kind of correlation research doesn’t refute what I’m saying.

What do you think psychometricians have been doing for the last 100 years?

Remaining ignorant of philosophy, particularly epistemology, as well as the theory of computation.

It is certainly true that one can create culturally biased IQ test questions. This issue has been studied to death, and such questions have been ruthlessly removed from IQ tests.

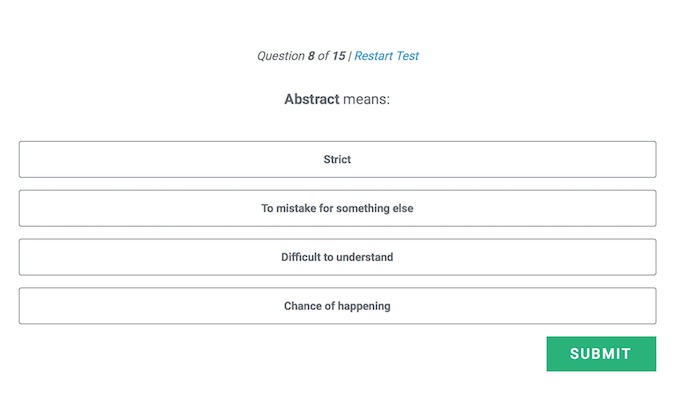

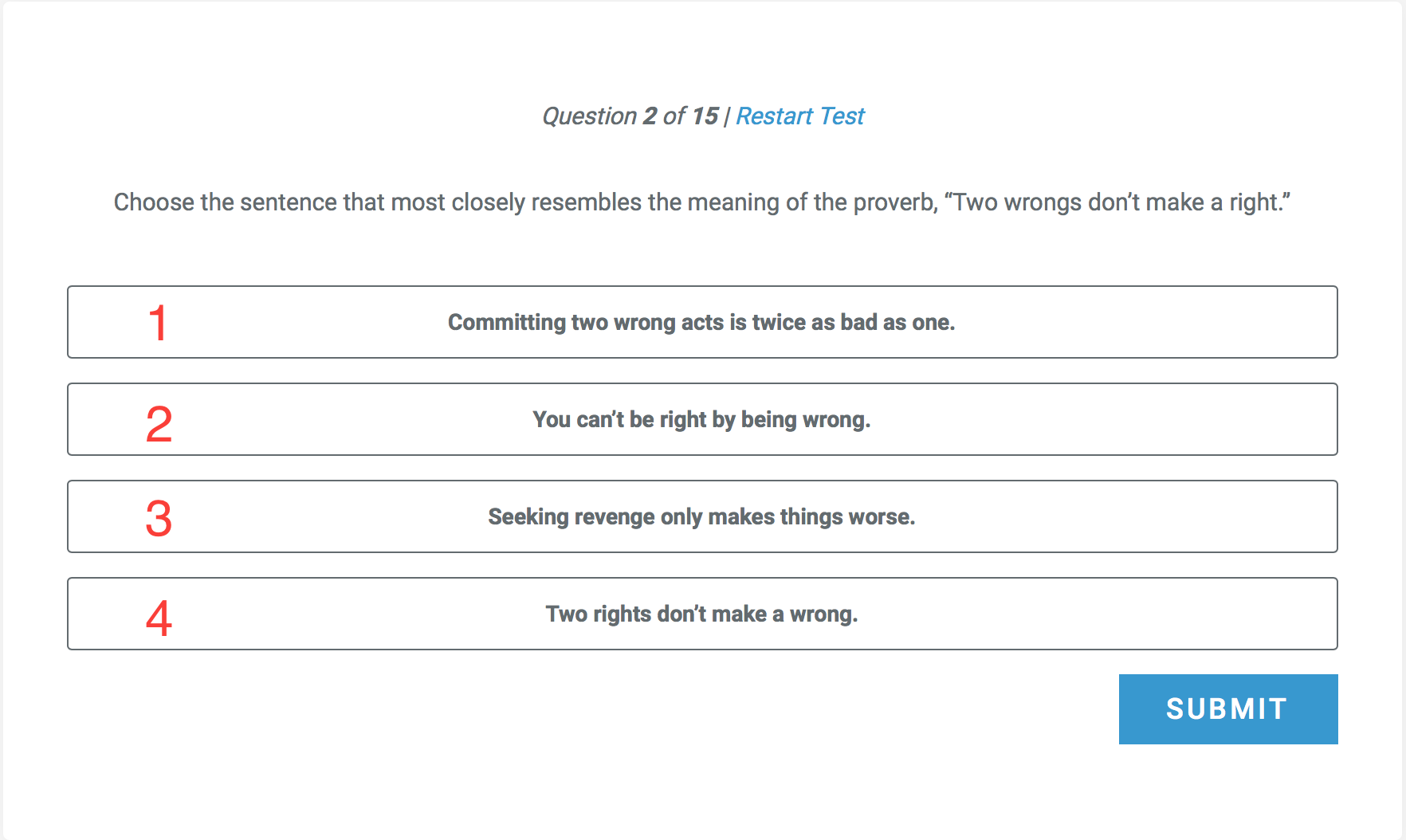

They haven’t been removed from the version of the Wonderlic IQ test you chose to link, which I took my example from.

I think there’s an important issue here. I think you believe there are other IQ tests which are better. But you also believe the Wonderlic is pretty good and gets the roughly same results as the better tests for lots of people. Why, given the flawed question I pointed out (which had a lot more wrong with it than cultural bias), would the Wonderlic results be similar to the results of some better IQ test? If one is flawed and one isn’t flawed, why would they get similar results?

My opinion is as before: IQ tests don’t have to avoid cultural bias (and some other things) to be useful, because culture matters to things like job performance, university success, and how much crime an immigrant commits.

I don't use the term "genetic" because I don't mean "genetic", I mean "heritable," because the evidence supports the term "heritable."

The word "heritable" is a huge source of confusion. A technical meaning of "heritable" has been defined which is dramatically different than the standard English meaning. E.g. accent is highly "heritable" in the terminology of heritability research.

The technical meaning of “heritable” is basically: “Variance in this trait is correlated with changes in genes, in the environment we did the study in, via some mechanism of some sort. We have no idea how much of the trait is controlled by what, and we have no idea what environmental changes or other interventions would affect the trait in what ways.” When researchers know more than that, it’s knowledge of something other than “heritability”. More on this below.

I have not read the articles you reference on epistemology, but intelligence has nothing to do with epistemology, just as a computer's hardware has nothing to do with what operating system or applications you run on it.

Surely you accept that ideas (software) have some role in who is smart and who is a moron? And so epistemology is relevant. If one uses bad methods of thinking, one will make mistakes and look dumb.

Epistemology also tells us how knowledge can and can’t be created, and knowledge creation is a part of intelligent thinking.

OF COURSE INTELLIGENCE IS BASED ON GENES, because humans are smarter than chimpanzees.

I have a position on this matter which is complicated. I will briefly give you some of the outline. If you are interested, we can discuss more details.

First, one has to know about universality, which is best approached via the theory of computation. Universal classical computers are well understood. The repertoire of a classical computer is the set of all computations it can compute. A universal classical computer can do any computation which any other classical computer can do. For evaluating a computer’s repertoire, it’s allowed unlimited time and data storage.

Examples of universal classical computers are Macs, PCs, iPhones and Android phones (any of them, not just specific models). Human brains are also universal classical computers, and so are the brains of animals like dogs, cows, cats and horses. “Classical” is specified to omit quantum computers, which use aspects of quantum physics to do computations that classical computers can’t do.

Computational universality sounds very fancy and advanced, but it’s actually cheap and easy. It turns out it’s difficult to avoid computational universality while designing a useful classical computer. For example, the binary logic operations NOT and AND (plus some control flow and input/output details) are enough for computational universality. That means they can be used to calculate division, Fibonacci numbers, optimal chess moves, etc.

There’s a jump to universality. Take a very limited thing, and add one new feature, and all of a sudden it gains universality! E.g. our previous computer was trivial with only NOT, and universal when we added AND. The same new feature which allowed it to perform addition also allowed it to perform trigonometry, calculus, and matrix math.

There are different types of universality, e.g. universal number systems (systems capable of representing any number which any other number system can represent) and universal constructors. Some things, such as the jump to universality, apply to multiple types of universality. The jump has to do with universality itself rather than with computation specifically.

Healthy human minds are universal knowledge creators. Animal minds aren’t. This means humans can create any knowledge which is possible to create (they have a universal repertoire). This is the difference between being intelligent or not intelligent. Genes control this difference (with the usual caveats, e.g. that a fetal environment with poison could cause birth defects).

Among humans, there are also degrees of intelligence. E.g. a smart person vs. an idiot. Animals are simply unintelligent and don’t have degrees of intelligence at all. Why do animals appear somewhat intelligent? Because their genes contain evolved knowledge and code for algorithms to control animal behavior. But that’s a fundamentally different thing than human intelligence, which can create new knowledge rather than relying on previously evolved knowledge present in genes.

Because of the jump to universality, there are no people or animals which can create 20%, 50%, 80% or 99% of all knowledge. Nothing exists with that kind of partial knowledge creation repertoire. It’s only 100% (universal) or approximately zero. If you have a conversation with someone and determine they can create a variety of knowledge (a very low bar for human beings, though no animal can meet it), then you can infer they have the capability to do universal knowledge creation.

Universal knowledge creation (intelligence) is a crucial capability our genes give us. From there, it’s up to us to decide what to do with it. The difference between a moron and a genius is how they use their capability.

Differences in degrees of human intelligence, among healthy people (with e.g. adequate food) are due to approximately 100% ideas, not genes. Some of the main factors in early childhood idea development are:

- Your culture’s anti-rational memes.

- The behavior of your parents.

- The behavior of other members of your culture that you interact with.

- Sources of cultural information such as YouTube.

- Your own choices, including mental choices about what to think.

The relevant ideas for intelligence are mostly unconscious and involve lots of methodology. They’re very hard for adults in our culture to change.

This is not the only important argument on this topic, but it’s enough for now.

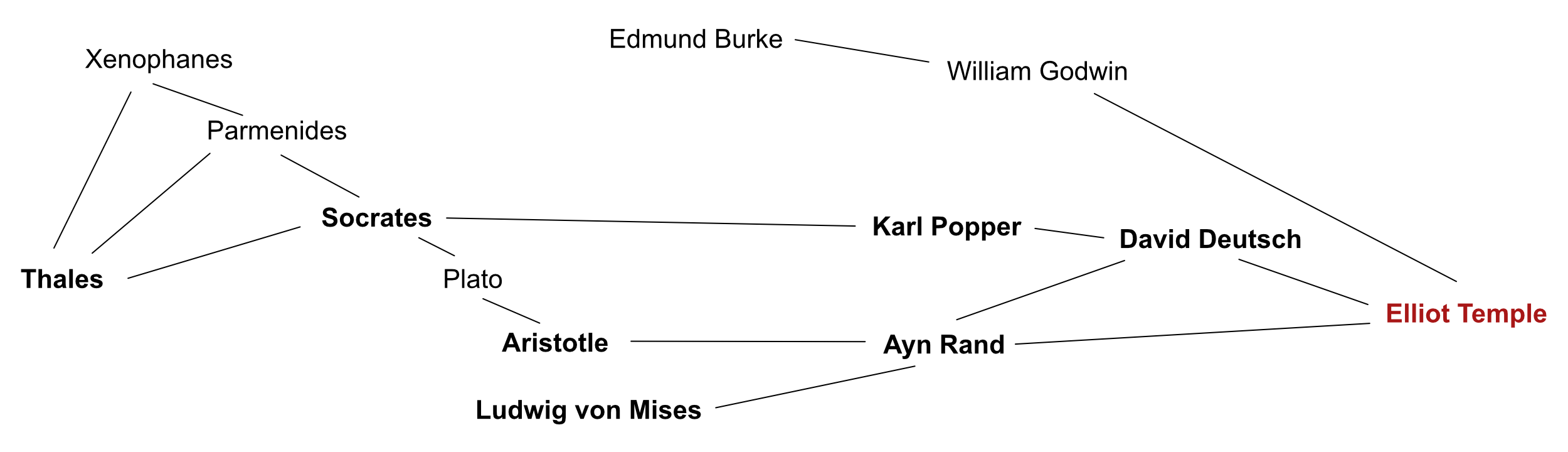

This isn’t refuted in The Bell Curve, which doesn’t discuss universality. The concept of universal knowledge creators was first published in 2011. (FYI this book is by my colleague, and I contributed to the writing process).

Below I provide some comments on The Bell Curve, primarily about how it misunderstands heritability research.

There is a most absurd and audacious Method of reasoning avowed by some Bigots and Enthusiasts, and through Fear assented to by some wiser and better Men; it is this. They argue against a fair Discussion of popular Prejudices, because, say they, tho’ they would be found without any reasonable Support, yet the Discovery might be productive of the most dangerous Consequences. Absurd and blasphemous Notion! As if all Happiness was not connected with the Practice of Virtue, which necessarily depends upon the Knowledge of Truth.

EDMUND BURKE A Vindication of Natural Society

This is a side note, but I don’t think the authors realize Burke was being ironic and was attacking the position stated in this quote. The whole work, called a vindication of natural society (anarchy), is an ironic attack, not actually a vindication.

Heritability, in other words, is a ratio that ranges between 0 and 1 and measures the relative contribution of genes to the variation observed in a trait.

This is incomplete because it omits the simplifying assumptions being made. From Yet More on the Heritability and Malleability of IQ:

To summarize: Heritability is a technical measure of how much of the variance in a quantitative trait (such as IQ) is associated with genetic differences, in a population with a certain distribution of genotypes and environments. Under some very strong simplifying assumptions, quantitative geneticists use it to calculate the changes to be expected from artificial or natural selection in a statistically steady environment. It says nothing about how much the over-all level of the trait is under genetic control, and it says nothing about how much the trait can change under environmental interventions. If, despite this, one does want to find out the heritability of IQ for some human population, the fact that the simplifying assumptions I mentioned are clearly false in this case means that existing estimates are unreliable, and probably too high, maybe much too high.

Note that the word “associated” in the quote refers to correlation, not to causality. Whereas the authors of The Bell Curve use the word “contribution” instead, which doesn’t mean “correlation” and is therefore wrong.

Here’s another source on the same point, Genetics and Reductionism:

high [narrow] heritability, which is routinely taken as indicative of the genetic origin of traits, can occur when genes alone do not provide an explanation of the genesis of that trait. To philosophers, at least, this should come as no paradox: good correlations need not even provide a hint of what is going on. They need not point to what is sometimes called a "common cause". They need not provide any guide to what should be regarded as the best explanation.

You can also read some primary source research in the field (as I have) and see what sort of “heritability” it does and doesn’t study, and what sort of limitations it has. If you disagree, feel free to provide a counter example (primary source research, not meta or summary), which you’ve read, which studies a different sort of IQ “heritability” than my two quotes talk about.

What happens when one understands “heritable” incorrectly?

Then one of us, Richard Herrnstein, an experimental psychologist at Harvard, strayed into forbidden territory with an article in the September 1971 Atlantic Monthly. Herrnstein barely mentioned race, but he did talk about heritability of IQ. His proposition, put in the form of a syllogism, was that because IQ is substantially heritable, because economic success in life depends in part on the talents measured by IQ tests, and because social standing depends in part on economic success, it follows that social standing is bound to be based to some extent on inherited differences.

This is incorrect because it treats “heritable” (as measured in the research) as meaning “inherited”.

How Much Is IQ a Matter Genes?

In fact, IQ is substantially heritable. [...] The most unambiguous direct estimates, based on identical twins raised apart, produce some of the highest estimates of heritability.

This incorrectly suggests that IQ is substantially a matter of genes because it’s “heritable” (as determined by twin studies).

Specialists have come up with dozens of procedures for estimating heritability. Nonspecialists need not concern themselves with nuts and bolts, but they may need to be reassured on a few basic points. First, the heritability of any trait can be estimated as long as its variation in a population can be measured. IQ meets that criterion handily. There are, in fact, no other human traits—physical or psychological—that provide as many good data for the estimation of heritability as the IQ. Second, heritability describes something about a population of people, not an individual. It makes no more sense to talk about the heritability of an individual’s IQ than it does to talk about his birthrate. A given individual’s IQ may have been greatly affected by his special circumstances even though IQ is substantially heritable in the population as a whole. Third, the heritability of a trait may change when the conditions producing variation change. If, one hundred years ago, the variations in exposure to education were greater than they are now (as is no doubt the case), and if education is one source of variation in IQ, then, other things equal, the heritability of IQ was lower then than it is now.

...

Now for the answer to the question, How much is IQ a matter of genes? Heritability is estimated from data on people with varying amounts of genetic overlap and varying amounts of shared environment. Broadly speaking, the estimates may be characterized as direct or indirect. Direct estimates are based on samples of blood relatives who were raised apart. Their genetic overlap can be estimated from basic genetic considerations. The direct methods assume that the correlations between them are due to the shared genes rather than shared environments because they do not, in fact, share environments, an assumption that is more or less plausible, given the particular conditions of the study. The purest of the direct comparisons is based on identical (monozygotic, MZ) twins reared apart, often not knowing of each other’s existence. Identical twins share all their genes, and if they have been raised apart since birth, then the only environment they shared was that in the womb. Except for the effects on their IQs of the shared uterine environment, their IQ correlation directly estimates heritability. The most modern study of identical twins reared in separate homes suggests a heritability for general intelligence between .75 and .80, a value near the top of the range found in the contemporary technical literature. Other direct estimates use data on ordinary siblings who were raised apart or on parents and their adopted-away children. Usually, the heritability estimates from such data are lower but rarely below .4.

This is largely correct if you read “heritability” with the correct, technical meaning. But the assumption that people raised apart don’t share environment is utterly false. People raised apart – e.g. in different cities in the U.S. – share tons of cultural environment. For example, many ideas about parenting practices are shared between parents in different cities.

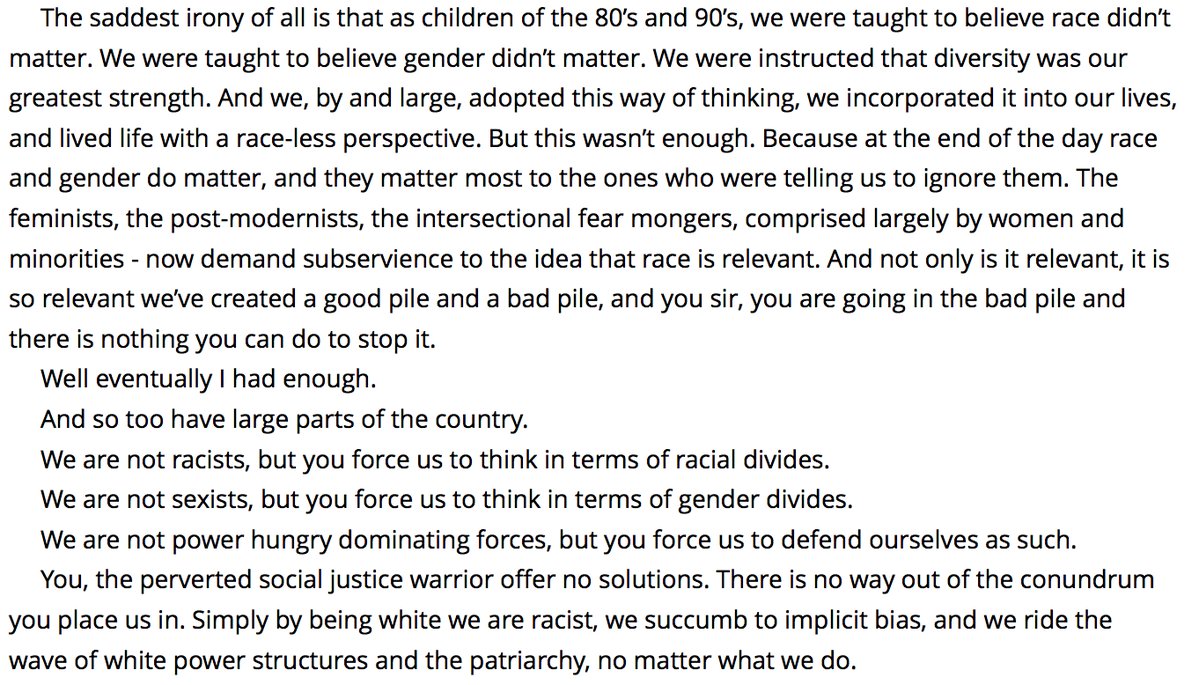

Despite my awareness of these huge problems with IQ research, I still agree with some things you’re saying and believe I know how to defend them correctly. In short, genetic inferiority is no good (and contradicts Ayn Rand, btw), but cultural inferiority is a major world issue (and correlates with race, which has led to lots of confusion).

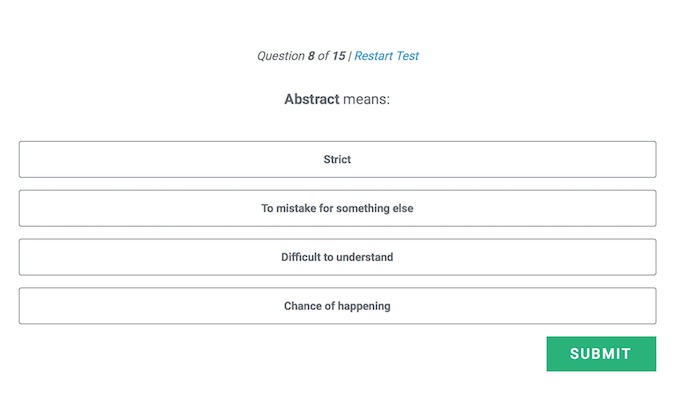

As a concrete reminder of what we’re discussing, I’ll leave you with an IQ test question to ponder:

Read my followup post: IQ 3